This week we’re back to one of my favorite topics: education. This is the second installment in a two-part series on the economics of education. For new subscribers, I’d recommend reading my first post on this topic here before continuing.

Much of the following is a condensed version of a paper I wrote while I was at Duke. For those interested, you can find that paper here.

In a previous post I wrote about an interesting problem in education: what’s the effect of high-ability students leaving to private schools on the peers they leave behind? Though this question itself is interesting, most “good” data (more on what constitutes “good data” in another post) surrounding this topic (and peer effects in general) is often only observable at the high school and college level. When I was first introduced to this topic and the Economics of Education, I was often left wondering about experiments at the elementary school level.

It’s no surprise that our early educational experiences have significant effects on development. From a human capital perspective, the returns to investing in elementary education versus higher education are – in many ways – (on the margin of course) much higher and perhaps easier to attain (more on this in another post – see here for a high-level explanation). There’s a famous paper written by the Harvard economist Raj Chetty (who, by the way, should win a Nobel – if he doesn’t I’ll personally petition the committee) which tracks elementary classroom quality to future earnings. This paper (and Chetty’s research findings broadly) have been written about ad nauseam in the press, but to give you a snapshot here’s the high-level finding from his groundbreaking paper:

“Students who were randomly assigned to higher quality classrooms in grades K-3 earn more, are more likely to attend college, save more for retirement, and live in better neighborhoods… increasing class quality by one standard deviation of the distribution within schools raises earnings by $1,520 (9.6%) at age 27. Under the preceding assumptions, this translates into a lifetime earnings gain of approximately $39,100 for the average individual. For a classroom of twenty students, this implies a present-value benefit of $782,000 for improving class quality for a single year by one (within-school) standard deviation”

Seems obvious, right? Yes. In this case, the conventional wisdom is, in fact, correct. The quality of one’s early education has a significant impact on future outcomes.

After reading a couple more Chetty papers I was inspired to take my initial question about kids leaving for private schools a step further. Instead of focusing on the effect of these students leaving, perhaps it’s better to first understand who leaves elementary schools in the first place and, potentially, why they might leave.

Ideally, to study a question like this we’d like data on some sort of randomized experiment where students are randomized into classes and tracked throughout elementary school. This way, we can track which students leave irrespective of characteristics unique to themselves, their parents, their school, etc. Crazy enough, there’s a widely cited experiment just for this: Tennessee’s Project STAR.

I’m not sure how this experiment was even approved (it’s also highly unlikely such an experiment would get approved today), but for researchers, Project STAR has been a blessing.

Project STAR was a class-size randomization experiment across grades K-3 in Tennessee held between 1985-1989. About 11,500 students across 75+ schools voluntarily participated. If you were a student in this experiment it went something like this:

Your school signs up for the experiment

At the beginning of Kindergarten you’re randomized into one of three class types:

small classes (13-17 students)

regular-sized classes (22-25 students)

regular-sized classes with a teacher’s aide (22-25 students in addition to a full-time teacher’s

aide)The idea here was originally to measure the effects of class size on test scores, but the data (as you might notice) can be used for a variety of purposes

You are kept in the same class between grades K-3 (i.e., everyone in your Kindergarten class is also in your 1st-grade class, your 2nd-grade class, etc.)

Both at the beginning and the end of the year, you take a battery of tests to measure your educational attainment

A comprehensive set of data is collected every year on characteristics related to yourself, your school, and your teacher (e.g., Teacher years of experience, student demographics, % of students in school on free lunch, etc.)

Without going too deep into the intricacies of randomization, I will address one concern that might be top of mind right now. Let’s say there’s a parent and her name is Becky. Becky has a child, let’s call them student A. Becky, being a good mother, looks out for her child’s educational welfare and wants the best possible experience for her kids. Something like this ensues:

Becky drives to student A’s elementary school in early August to take a look at the class lists posted outside the office for the upcoming school year

Becky soon realizes student A has been placed in a “large classroom”

Becky, disappointed that her child won’t be in the smaller class – where she believes student A will receive more attention calls up her schools principal

A conversation ensues between Becky and the principal where Becky pleads with the principal to let student A switch to a smaller class

This scenario, although rare, did happen. To correct for this, students were re-randomized into classrooms and any student who entered a classroom midway through the experiment was also randomized into a classroom. This prevented parents like Becky from trying to switch their children to another school to place them in a smaller classroom and ensured the randomization was well-designed.

Let’s turn back to my original question: what kinds of students leave elementary school and why?

I posit that there are two channels of attrition:

Low-income (often low-ability) students leave schools for a variety of reasons including migration, familial instability, loss of a home, etc.

High-income (often high-ability) students leave for private schools either through migration or cream-skimming

This seems to be correct – there’s only two buckets of reasons I’d consider to change my childs elementary school:

The family moves (usually from upward economic mobility) or I place my child in a school that’s better for them – that is, this bucket is comprised of moving to a better school

I am unable to continue to put my child in school due to unforeseen circumstances

We’d think that, in general, students that fall into group 1 are of higher ability (e.g., leaving to a gifted program) and higher income whereas students in group 2 are the opposite. From my research, it’s clear both channels exist, though channel 2 significantly dominates channel one.

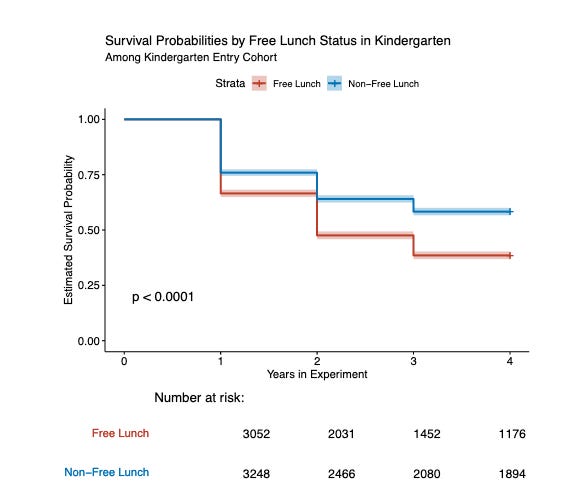

To illustrate, take a look at the following charts. Here, the y-axis represents the probability of staying in Project STAR (i.e., the lower the line is, the more students from that group left) and the x-axis represents years in the experiment. From both of the following images, we see that students in the bottom 25th percentile of test scores and those of lower income were less likely to stay in the experiment.

To provide a bit more of a rigorous look – here’s a decomposed grouping of students who left Project STAR I analyzed using clustering:

As you can see, groups 4 and 5 seem to be made up of higher-income, higher-ability students, and groups 1, 2, 3, and 6 seem to be of lower income and lower ability. Though I also tried to measure the effects of this attrition on the peers they leave behind, that research was inconclusive. A discussion of bias and other modeling intricacies can be found if you read the whole paper.

More importantly, what’s the importance of knowing these channels exist? There’re two things that come to mind:

Teachers should be worried about students who are at risk of leaving elementary school. This risk is twofold:

If high-ability students leaving has a negative impact on peers, teachers should attempt to enrich these students in order to mitigate their incentive to leave

Low-ability students who may be at risk of not completing their education should potentially be “cross-subsidized” by higher-income students (i.e., higher-income students “pay” to keep lower-income students in school – this method is quite common in private schools and colleges, where students on full-tuition cross-subsidize aid for lower-income students)

An analysis of educational outcomes and policy should center on the indirect effects of education – namely peer-to-peer spillovers caused by things such as attrition rather than a focus on how to improve educational output (i.e., if smaller classrooms produce higher test scores)

On the margin, perhaps, it might be easier to keep a student in school rather than hire more teachers or resources to put them in a smaller class (in this case, the future earnings loss to the student who leaves is greater than the potential earnings benefit of being in a smaller class)

The real idea here is the tradeoff between hiring additional teachers or building additional classrooms and something akin to free lunch programs, after-school activities, or hiring a school counselor to provide incentives to keep students in school

Taking an approach where the largest negative effects (i.e., a student leaving the school system) are prevented potentially provides greater gains than large-scale resource allocation schemes which aim to sort students in such a way that improves their test scores

Regardless, we need to place greater emphasis on the returns to human capital – perhaps through an investing framework. If we think about educational policies in terms of returns for every unit invested, rather than just the headline figures, perhaps things might change.

This post (hopefully) brings up many points for discussion, some of which I intend to write about in future pieces. See you next week!

Thanks for reading!

If you enjoyed this piece, please click the like button, leave a comment, and share it with friends 😀