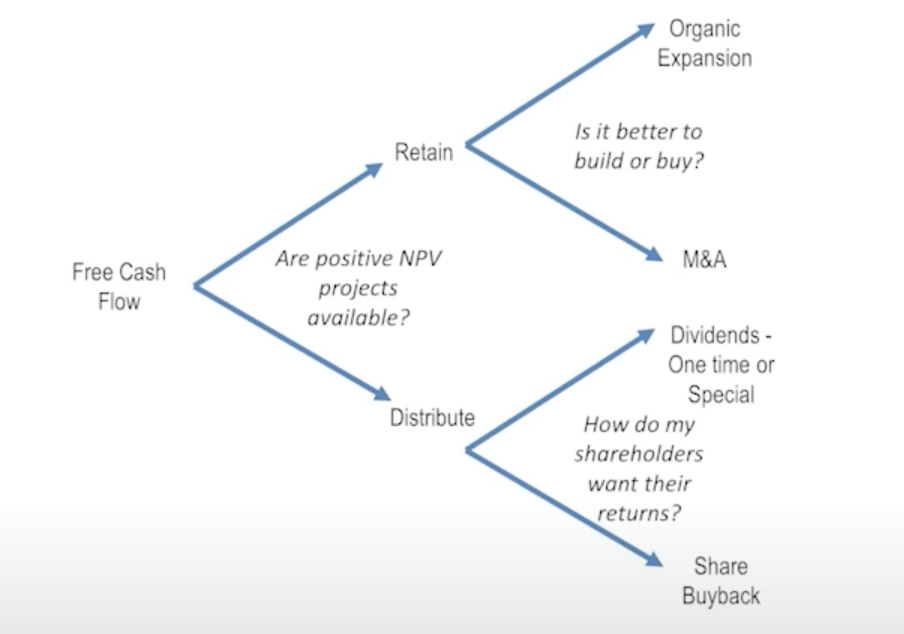

I think every CEO and investor (and wannabe CEO and investor) should have a printout of this chart framed in their office. I came across this while watching Mihir Desai’s “How Finance Works” lecture at the Rotman School of Management.

Full credit to Mihir, he’s distilled what I once thought was an extremely complicated and mystical decision into a simple set of choices. That decision? Capital Allocation.

Imagine you are the CEO of a public company. Say for these purposes your company “Cut Away Inc.” manufactures scissors. Every day you walk into your office and have to consider the following question: “What do I do with all the cash sitting on my balance sheet?” More often than not, the answer to this question does not require the “expertise” of a McKinsey consultant – it's actually quite simple.

In a vacuum, a CEO’s primary job is to deliver returns to its shareholders. As the CEO of Cut Away Inc., your scissor business is booming. It’s the golden age of printout birthday coasters, and schoolchildren are finding your scissors all the rage as they snip their way through birthday parties. Your business is performing well and you are flush with cash. As such, you ask yourself: “What should I do with all this money?”

Enter Mihir’s chart – as he explains, an allocator of capital has two choices:

Grow the business

Distribute money to shareholders

The key point is that 1 and 2 usually cannot function at the same time. If you are investing capital to grow your business, the return threshold (or hurdle) required by those expansion projects is necessarily higher than that which you would be able to provide to your shareholders through a distribution. In English – the money you invest for the future will someday be worth more to someone than the money you would distribute today. More on this later.

Let’s start with #1. Growth opportunities come in many forms, but instead of thinking of growth as new ways to generate revenue, think of growth as ways to realize efficiencies or scale in your business. In our case with scissors that may be the following:

Achieving cost efficiencies by either scaling production to increase the utilization of a factory or running a “leaner” firm by reducing headcount

Developing a new “scissor technology” or other product which turns into a new revenue stream

Undertaking a new marketing strategy to deliver increased performance in a new market or demographic

Growing inorganically either vertically or horizontally

Each of these (non-exhaustive) options all function as a way of increasing the amount of cash a business is generating. Each strategy has associated with it a set return that can be realized over a set period of time. All else equal, the undertaking of a cost-savings plan aiming to increase cash flows by 1% every year for 10 years can be viewed similarly to the acquisition of a company aiming to produce a new revenue stream that increases cash flows by 1% every year for 10 years.

Instead of thinking about a growth lever as an “unlock” which will “increase the speed of our growth flywheel” view the associated monetary gains with each of these strategies as interest payments on a bond. With higher-risk strategies such as developing a new product, you aim to achieve higher compounded returns in perpetuity with higher upfront costs (aka more “downside risk” aka “more money to lose). The opposite is the case for their lower-risk counterparts in the discovery of operational efficiencies in the underlying business. At the end of the day, undertaking route #1 allows your scissor company to achieve one of the following:

Increase the future value of the enterprise given the business’ quality

Produce more cash flow either due to margin expansion or increased revenues

Have the ability to take on higher risk (and higher reward) endeavors without hampering the cash needs of the business (i.e., allow yourself room for experimentation)

Of all of these 3 achievements, #3 is perhaps the hardest but most important to understand. To understand the payoff of any of these decisions, we have to compare them in accordance with the associated risk profile of each avenue of growth. For those that aren’t familiar with the concept of discounting, think of it like this:

Money today is worth more than money tomorrow

If I invest 1$ in a project to build a new scissor factory, that 1$ could go to 0, turn into 100 or stay worth 1$. It’s important to understand that due to the uncertainty associated with each option I have to spend 1$, I have to measure the “true value” of a dollar today based on what might happen to my dollar tomorrow

Depending on what I do with my money, the associated “reward” must be commensurate to the relative level of “risk” I take on – as such, there must be some opportunity cost associated with the choice to spend my 1$ tomorrow on one growth strategy vs. another

Think of it like this: You and your friend both go out to eat. Your friend has no money so you lend them 10$. Your friend, being generous, says that they’ll pay you back an extra dollar for spotting them this time in a week when they get their allowance. Depending on your time preferences (i.e., how soon you need that 10$ back) and how much you believe your friend will stick to their word, that 10$ tomorrow will (in most circumstances) be worth less than that 10$ to you today.

How much less? Well that’s determined by your “discount rate” (aka, the return required for you to be happy waiting to get your money plus an additional dollar back)

This rate, which expresses the “preference” for one project over another (i.e., a measure of its required return in excess of the “risk-free” choice) represents the rate at which I should discount the future gains associated with a growth investment to determine if it would be profitable today

If that rate of growth (i.e., the “NPV” or present value of the future gains of the project) of any project is positive and greater than any return I could distribute to my shareholders today, I should undertake the growth opportunity. For stakeholders or advisors trying to convince a CEO to charge down a desired path to growth, simply prove to them that the gains associated with this investment are greater than any gain a shareholder could expect today in the form of a distribution.

Key to this is understanding what the right “discount rate” is – but perhaps more interesting (and maybe more important) is how to view a business when they flip from retaining capital to investing capital.

Let’s take the example of our scissor company. As CEO, you’ve done an amazing job over the past 10 years growing the business. You’ve acquired a robotics company to help assist in modernizing your production, invested successfully in new strategies to grow outside the U.S. market, and undertaken a period of “operational excellence” right-sizing your management team and drastically improving the efficiency of your business. Now as you’ve “done all you possibly can” you think decide to turn on the “buyback switch” and start continuously returning capital to shareholders. You decide to issue a dividend and grow it meaningfully year over year while also turning to buy back shares.

At this point, you are hungry for cash you can use either buy back your shares or distribute them in the form of a dividend. No longer interested in borrowing money or utilizing cash on hand to finance projects you turn to something sexier, the joint venture.

I will perhaps write a longer post eventually about this structure but think of it like this:

The scissor company wants to save cash that it can use to buyback shares or distribute a dividend

Some “low cost of capital” (aka low return threshold) pension fund or private equity firm has a significant amount of cash to throw at a project

You, as CEO of Cut Away Inc., decide to partner with an external investor to fund the creation of a new joint venture:

This venture will be independent of Cut Away Inc. and owned 50/50 by both the company and the external investor

All investment into this joint venture will be split 50/50 by both parties and any profits will be similarly distributed

No debt will be raised by Cut Away Inc. as part of this transaction, categorizing all actives of the joint venture under the elusive category of am “off-balance sheet investment” (aka “not my responsibility”)

After 5 years, Cut Away Inc. has the option to “buy out” the external investor and consolidate the JV into the larger company if they want to

Why do this? It's simple:

Let’s turn back to Mihir’s chart: as CEO you have two options:

Redistribute your cash

Reinvest the cash in the business

As a shareholder of this company, you would always prefer #2 to #1 so long as the NPV of the future cash flows associated with the growth project is less than the current amount the company can distribute today. In this case, entering into this partnership allows you to fund projects with less of your capital, retaining cash flow to pay a dividend or engage in a buyback while also earning a modest return on your invested cash.

Being able to both distribute capital and engage in growth is a win-win for your business, which is why this structure has become more and more attractive. Not only are you continuing to distribute capital to your shareholders, but you are also funding the future growth of your business in a “de-risked” manner by partnering with an external investor.

As nice as this sounds, the entrance into projects like this is precisely the sign of a dying business. The only reason why a company would enter into this agreement is such that the cost of capital required to invest in it yourself is too high that you require a partner’s assistance. The only case in which a company would willingly accept a lower return on investment is if they either:

Do not have the cash to fund it themselves (either by being too small or too indebted)

Have exhausted all other growth avenues

When large, public companies tied to their dividends and buybacks enter projects like this (see here, here, and here). It’s what I see as a clear sign of a dying business. That’s not to say buybacks and dividends are bad. In fact, they’re great. It’s to say that when a company decides to prioritize distributions over growth, it's often a sign of larger, structural issues with the business that may be starting to apperar.

Capital allocation is a critical decision that CEOs and investors have to make when weighing how to maximize both a company's growth and shareholder returns. While there may be legitimate reasons to distribute cash to shareholders, consistently prioritizing distributions over growth opportunities can signal a lack of long-term vision and confidence in the business's ability to generate future cash flows. Furthermore, a sudden shift from retaining to distributing capital may be a sign of a dying business, as it could indicate a lack of profitable investment opportunities or an inability to generate sustainable cash flows.

When CEOs shift their focus from retaining to distributing capital, they are signaling to investors that their company has exhausted its growth opportunities and can no longer generate sufficient returns through internal investments. A company that has hit a growth ceiling is like a plant that has outgrown its pot - it won't thrive and produce fruit unless it's transplanted into a bigger one. Sometimes, there just isn’t a bigger pot out there - CEOs will signal when they’ve reached the end of the road, don’t be there catching the falling knife.

I know it’s been a bit since the last post. It’s been a busy couple of months for me but I’m back and ready to continue writing. Expect more in the future.

DISCLAIMER

The content provided on the “Sanjay’s Substack” newsletter is for general informational purposes only. No information, materials, services, and other content provided in this post constitute solicitation, recommendation, endorsement or any financial, investment, or other advice. Seek independent professional consultation in the form of legal, financial, and professional advice before making any investment decision. Always perform your own due diligence.