In a previous post, I spoke about incentive problems in the private equity industry. Although I do believe these risks are significant for most large LPs, I want to be clear that these risks in fund structure are mostly isolated to what we would call “Megafunds” and “Upper Middle Market Funds” (aka funds that are at least $2.5B in size). That said, in a world where markets are getting more efficient and algorithmically-driven trading is taking over, I believe alternative investments – especially private equity – will see significant tailwinds in the form of what I call “behavioral” alpha. As I know most of my readers aren’t too familiar with the world of “high-finance” I’ll give a short primer on private equity, hedge funds, and alpha to help illustrate this observation:

One quick note for my finance friends – a nuanced discussion surrounding this topic involves an educated view of the efficiencies of markets and whether or not “alpha” can truly exist. For the purposes of this piece I’m going to assume real-life equity markets are inefficient and information asymmetries – although much harder to find today than 50 years ago – do exist.

For those unfamiliar there are two markets through which one can invest:

Public Markets (aka the “stock” market) where ownership can be bought in public companies

Private Markets (aka every company that isn’t public)

For example, buying shares of Apple constitutes participation in public markets. Selling a non-public family business constitutes participation in private markets.

To keep it very simple, let’s think of a hedge fund as a fund that invests in the shares of public market companies. Its structure and strategy are something akin to the following:

You source a pool of money from outside investors (might be yourself, high net worth individuals, large pension funds, etc.)

You then invest this money in an asset class of your choice – in this case, Public U.S. Stocks

You apply some strategy to pick stocks that you believe will perform well or bet against companies that you believe won’t do well. This might be in the form of:

Looking for “undervalued” companies that the market has overlooked

Place bets on “growing” companies that may not be profitable which the investor believes will become successful in the future

Look for potential sources of fraud and bet against these companies

And others

Rinse and repeat, continuing to buy and sell stocks as you try to produce outsized returns

The goal of a hedge fund is to beat what we call a “benchmark.” Think of this as the following:

If your fund invests in public U.S. companies, we’d want to compare it to the return of the entirety of the public U.S. market

That is, the allure of investing in a hedge fund is that one will outperform the market

If your hedge fund beats its benchmark – congratulations! You’ve produced alpha.

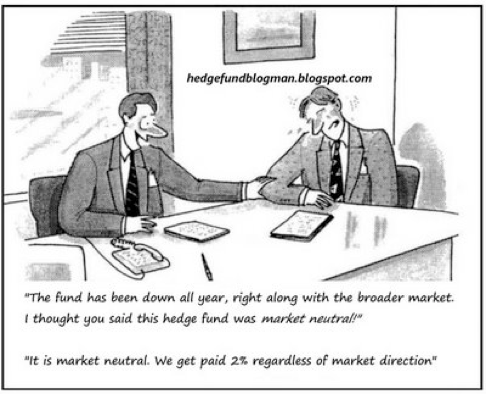

Ideally the relationship here is that the hedge fund takes a fee for the performance of its investments (similar to a private equity firm) and net of fees the fund beats its benchmark – though this rarely happens

Obviously, there are different benchmarks for different types of funds

A credit fund would be compared against a benchmark of U.S. bonds

The same would be true for a foreign exchange fund, a commodity fund, etc. – these would be compared to benchmarks for their relative asset classes

Benchmarks serve as a measure of performance – the idea here is that if a fund isn’t beating its benchmark, perhaps I shouldn’t be paying them to invest my money

I mentioned this briefly, but alpha is the returns of a fund in excess of its benchmark. Alpha is the “golden fruit” of finance, it's what both investors and fund managers chase. If your fund is producing alpha, it means you’re doing better than the market, which means your money will compound faster. To put it very simply:

A fund returns 10% in a year when the overall market/its “benchmark” returns 8%

We would consider this fund to have beat its benchmark by 2% (aka 2% of “alpha was generated”)

Yes, I know the real formula for alpha adjusts for volatility, etc. but we’re keeping it simple here

Cool. So how does one produce alpha? Usually its some form of:

Investing Skill

Nuanced/Contrarian approach (aka “seeing what the market isn’t”)

Finding discrepancies in markets

Oh, and maybe having access to information you shouldn’t…

Let’s focus on that 3rd point for a second to illustrate something going on in public markets today.

You have a company whose stock trades on the U.S. stock exchange for $100/share

The same company’s stock trades for 10,000 Yen on the Japanese stock exchange (~$75)

In this situation, assuming the two shares are fungible (aka they are exactly the same thing, just one can be bought in Japan and another in the U.S.) a hedge fund may identify this opportunity and buy the stock in Japan and sell it in the U.S., netting the $25 difference as profit – risk-free

This kind of “arbitrage” strategy used to be quite prevalent in public markets. We can think of this as being extended to a company. Say you walk into stores around you and notice a certain beverage company’s drink is catching on – you have good evidence that this beverage will do well. As such, you invest in the company with your informational advantage. You reap your reward when the company announces earnings and reveals the success of its new drink.

These kinds of opportunities – which used to be quite common – are few and far between in today’s markets. Why? The rise of “quantitative investing” and the internet. Today, investors not only have access to ultrafast pricing data and exchange connections (eliminating the kind of pricing arbitrage I described before) but also highly-sophisticated prediction algorithms and access to troves of data on companies. Though I use the arbitrage example to illustrate the effect of better exchange technology and data flows on the information held by investors, the same can be applied to company valuation.

Today, I can get satellite imagery of Apple’s factories months before a new iPhone is released and predict the amount they have produced based on the number of trucks leaving the factory. I have access to every earnings call a company releases, their Twitter followers, NPS scores, engagement on social media platforms, google trends data, etc. The days of going into a Walmart and deducing their clientele by surveying those who come into the store are over. The abundance of information available today to investors makes it much harder to find “what the market isn’t seeing” – that is, information that would produce alpha (what we would call an “edge” in investing). This change provides new meaning to the idea of an “intelligent investor” far different than what Ben Graham described in the 1950s.

So, what does this mean for investors? That alpha is reduced. The more information asymmetries between market participants are reduced, the more returns will decrease. That idea is that if everyone knows what you know, your returns should theoretically converge together. The production of alpha is entirely dependent on one’s ability to know more than or be better than other market participants. If every market participant is already information-rich, it makes it much harder to beat your benchmark.

This is where private equity is different. Your basic private equity fund works like this:

You source a pool of money from outside investors (might be yourself, high net worth individuals, large pension funds, etc.)

You find a company – usually one that’s asset-light, rich in cash, and in a growing industry – which you look to buy using a combination of cash and debt (to “juice your returns” – think of this like mortgaging a house)

Once you take control of the company you “right-size” the business (aka cut costs, perhaps expand on a new product line, etc.) to produce as much cash as possible

After 3-5 years you look to sell the business to another interested party, take it public, or explore another exit strategy.

When operating in private markets – there are rampant informational asymmetries. As these companies are not required by a government body (e.g. the SEC) to report financials to the public, oftentimes the companies private equity firms target are “black boxes.” At the same time, given private equity funds are buying companies whole, they take full control of a company’s operations allowing them to shape and grow the business as they please.

Although this form of investing involves considerable risk, it is insulated from much of the “alpha-reducing” properties of public markets today. Most of this advantage comes at (in my opinion) the extremely small end of the private equity fund spectrum: funds with less than $500M in assets under management. There are a couple of reasons why. In my opinion, they stem from:

Private equity firms of that size provide significant liquidity to founders seeking an exit

Private equity operating partners can exert significant “digital transformation” and cost-cutting in what may be well-earning but inefficient businesses that haven’t seen returns to scale in their current state

Private equity funds have more entrenched connections to capital markets which may provide a boost for companies that need follow-on capital to grow – capital that they may not have received before

Let’s think of the following scenario:

A midwestern gentleman named John owns a meatpacking business, it's his family’s company which he began to run after his father retired

A private equity fund believes that they can grow this business from $10M in profit to $30 in 5 years through cost cutting, the implementation of software solutions, and more efficient operations

As such, the private equity fund believes that the business is worth something around $50M today

John is then approached by the private equity firm looking to buy his business

John, who has done well for himself is looking to leave and retire is interested in the offer. He imagines himself using the proceeds from a sale to build his family’s wealth and spend more time away from work

John, looking for liquidity, would be happy with a buyout of anything above $15M – for him, this represents a massive financial windfall

For the private equity firm, this is a delight! They can buy a business that they believe is worth $50M today for only $15-20M!

Through negotiation, the private equity fund convinces John to sell his business – netting both of them a win-win

The ability to negotiate and find untapped opportunities like these is rampant and will likely stay rampant within the smaller-end private markets. Even if more private equity funds enter the space – there are simply too many inefficient businesses led by liquidity-seeking founders for this pattern to not be repeated over and over again. At a certain fund size, there are “behavioral” advantages that private equity fund managers can leverage to produce returns. Think of these as encompassing:

Better management

Deal negotiation

“Implied Perks” (aka golf trips, nice dinners. Etc.)

Incentives for founders to sell (e.g., family preferences, life events, etc.) that play to the benefit of private equity funds

There is also a lot to be said for why John would trust a PE fund manager versus his family, who may not want him to sell the business

This potentially feeds into some interesting research around “weak ties” and opportunity, which is profiled here

As such, I think it's clear that small private equity funds may continue to produce outsized returns for investors long into the future while hedge funds will continue to underperform, especially those funds which choose not to partake in the “quantitative revolution” that has taken over markets (Luddites always lose). In markets that are less centralized and information-rich, opportunities for alpha generation will persist. That will be the staying power of private equity.

For more reading, please see the following on: the ETF/Passive investing revolution , the rise of high-frequency trading, the potential dominance of software private equity (51:11 onward), and quantitative investing strategies.

I hope you enjoyed this – will see you next post!